Power Transmission

Power Transmission in Québec

- Find out more!

The power system

The power system

and its interconnections

World first by Hydro-Québec

World first by Hydro-Québec

Electricity often travels over very long distances to reach urban load centres. For example, the distance between Baie-James region—where water from the Grande Rivière ends up after driving the turbines in eight power stations–and Montréal is about 1,000 kilometres as the crow flies. However, the farther electricity must travel, the greater the risk that part of it will be lost on the way. Since utilities invest heavily in the high-volume transmission of power over long distances, they take special steps to limit these transmission losses.

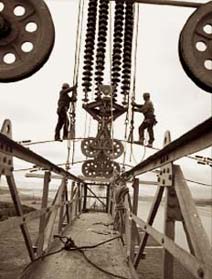

Live-line work: A power job

Live-line work: A power job

This technique consists in performing various maintenance tasks and repairs on high-voltage lines in totally safe conditions, but without de-energizing the lines. Since power transmission never ceases, utilities are able to avoid equipment downtime and the resulting losses of revenue.

735 kV anybody?

No problem! A lineman can work in a 735-kV environment, provided he follows the proper safety procedures. For example, special protective equipment— insulated aerial buckets, insulating sticks and insulating gloves—must be used to prevent electricity from flowing through the lineworker’s body to reach the ground.

High-voltage transmission, a solution perfected by Hydro-Québec

When moving large volumes of electricity, it’s better to increase voltage instead of current intensity (amperage), in order to reduce energy losses and limit the total cost of transmission (building additional power lines, for example). A large portion of the power generated by Hydro-Québec is transmitted using 735-kV lines. Without these high-voltage lines, the landscape would be cluttered with towers. One 735-kV line is equal to four 315-kV lines, the next voltage level down.

In fact, Hydro-Québec is a pioneer in high-voltage power transmission: it developed the world's first commercial 735-kV line, as well as the earliest equipment designed for that voltage.

In 1965, the first ever 735-kV power line was commissioned, linking the Manic-Outardes generating stations to the metropolitan areas of Québec and Montréal. This genuine breakthrough in the energy industry–technology invented by Québec engineer Jean-Jacques Archambault–was essential to developing hydroelectric projects in northwestern and northeastern Québec.

Direct-current transmission

The technology used to transmit direct current is not the most common. However, it can be advantageous for isolating alternating-current systems or controlling the quantity of electricity transmitted. Hydro-Québec has a direct-current line (which goes from the Baie-James region to Sandy Pond, near Boston) as well as many direct-current interconnections with neighboring systems.

Radisson substation

Live-line work:

Live-line work: Converter that transforms alternating current into direct current at Radisson substation.

Converter that transforms alternating current into direct current at Radisson substation.