1960-1979 – The Second Nationalization

After the Liberal government of Jean Lesage came to power in June 1960, it gave Hydro-Québec an exclusive mandate to develop and operate hydropower sites not yet under concession to private interests. On May 1, 1963, when the government authorized it to proceed with the gradual acquisition of private electricity distributors, Hydro-Québec finally achieved Québec-wide scope. The second stage of nationalization had begun. How could Hydro-Québec meet the demand for electricity, which was growing at a rate of about 7% a year? It would have to double its generating capacity every ten years. For that reason, Hydro-Québec built three major hydroelectric complexes in rapid succession: Manic-Outardes in the Côte-Nord region, Hamilton Falls (later renamed Churchill Falls) in Labrador, and the La Grande complex in the Baie-James region. Behind this accelerated development loomed the shadow of nuclear power, which by the mid-1960s had become the darling of the international energy scene. But the Québec Hydro-Electric Commission. continued to put its faith in hydropower.

1960

Carillon, a turning point for Hydro-Québec

Supervision of the work at Carillon, a state-of-the-art hydro project on the lower Rivière des Outaouais (Ottawa River), was assigned to French-speaking Hydro-Québec engineers. Francization was moving forward at the corporation’s head office and all its work sites. Carillon was also the project that confirmed Hydro-Québec’s policy of outsourcing its engineering needs, which spurred the creation and expansion of Québec-based consulting engineering firms.

Slide show

The following slide show contains images from the Carillon generating station

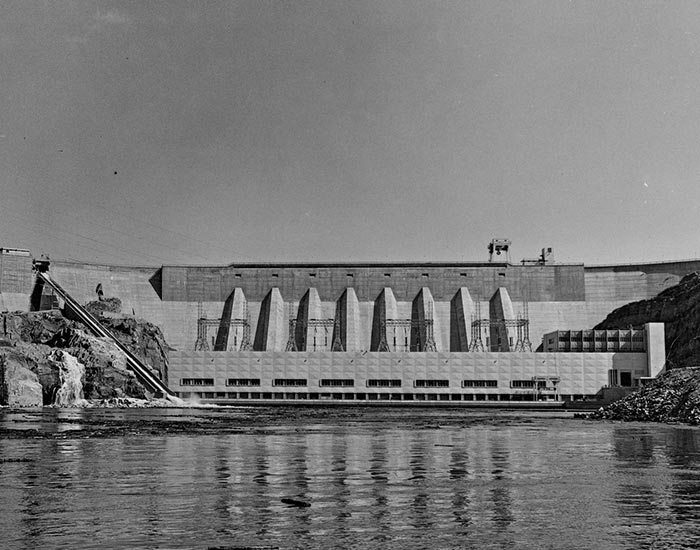

Manic-Outardes: technological feats

Begun the previous fall, work continued on the Manicouagan and Outardes. rivers, site of the most ambitious hydroelectric complex ever undertaken in Canada. The project gave rise to technical feats and world firsts that immediately raised Hydro-Québec’s international profile. On the initiative of a young engineer, Jean-Jacques Archambault., Hydro-Québec made a critical technological breakthrough in the long-distance transmission of large quantities of electricity by raising the voltage to a record level of 735 kV. At lower voltages, transmission losses would have been sizable and many more lines would have been required.

Slide show

The following slide show contains images from the Manic-Outardes

1962

René Lévesque drops a bombshell

On February 12, René Lévesque, then provincial Minister of Natural Resources, delivered a speech inaugurating National Electrical Week. To an audience that included executives of private electricity companies, he described the industry’s situation in Québec as an impossible and costly mess. He criticized the disparity in rates and unavailability of electricity which were slowing down the development of some regions of Québec; he deplored the small number of management positions open to French-speakers in the various utilities, and he stressed the overlapping responsibilities of private distributors, electricity cooperatives, municipal systems and self-generators (these last being mainly large pulp-and-paper or aluminum companies such as Alcan, whose plants were sited on rivers). Lévesque concluded that Hydro-Québec should be made responsible for the effective, orderly development of water resources and establishing uniform electricity rates throughout Québec.

A general election to avoid an impasse

René Lévesque's program was not unanimously accepted by Jean Lesage’s cabinet. To avoid an impasse, the Premier summoned cabinet members to a meeting at Lac-à-l’Épaule during the summer of 1962. After the meeting, Lesage called an election for November 14; this was the Québec electorate’s chance to say ‘yea’ or ‘nay’ to Hydro-Québec’s acquisition of private electricity distributors. Jean Lesage was re-elected, and Hydro-Québec acquired some 80 companies, private distributors, electricity cooperatives and municipal systems that accepted its buyout offer. The merger of all these companies into a unified whole—an operation of unprecedented scope and complexity in North America—took less than three years. Rates were gradually standardized. All the transmission system’s technical standards were studied and made uniform to ensure high-quality service for all customers, everywhere in the province.

Slide show

The following slide show contains images from the year 1962

1963

A successful takeover

Hydro-Québec, through successful takeover bids, acquired the private electricity distributors. As anticipated, the total cost of this second phase of nationalization was $604 million. Hydro-Québec took over the $250 million worth of bonds issued by the private companies. It recovered a little more than $50 million from the resale of assets unrelated to electric power. To reimburse the shareholders of the companies it acquired, Hydro-Québec sold $300 million in bonds on the American market. At the request of the American government, payment of the loan was spread over a period of more than a year, as a cushion against sudden changes in the exchange rate. The fact that Hydro-Québec consistently played by the rules while conducting this vast operation earned the new utility an enviable reputation in financial circles.

As this light bulb packaging shows, Hydro-Québec used all sorts of means to encourage farmers to use electricity.

Hydro-Québec historical collection

1996.0267

1965

Experimenting with nuclear technology

In the mid-1960s, the popularity of nuclear power was at its peak. Ontario Hydro, which had already developed all the water resources at its disposal, was involved in a vast program to construct power plants using the Canadian-designed CANDU nuclear reactor. A number of countries, including the United States, England, France, the Soviet Union and Germany, were developing their own nuclear reactors. To acquire expertise in what some were calling the energy of the future, Hydro-Québec signed an agreement with Atomic Energy of Canada Limited to build the experimental Gentilly-1 power plant, subsequently dismantled in 1977, and Gentilly-2, which closed in 2012. A moratorium in 1980 put construction of new nuclear power plants in Québec on hold. Around the same time, accidents at Three Mile Island in the United States (1979) and Chernobyl in the USSR (1986) dampened the world’s love affair with nuclear power.

Medal commemorating Gentilly-2 power plant.

Hydro-Québec historical collection

2005.0161

1966

The Churchill Falls power deal

On June 16, 1966, Premier Daniel Johnson, whose party had been in power less than two weeks, was faced with a difficult decision. Should he authorize Hydro-Québec to sign a letter of intent committing the government corporation to purchase nearly all the energy produced by the future Churchill Falls development in Labrador? This megaproject involved construction of a huge generating station, as powerful as all seven Manic-Outardes plants combined. Hydro-Québec tried in vain to get neighboring utilities in Canada and the United States to purchase some of the power to be produced at Churchill Falls, but these companies took the view that nuclear energy would be more economical than energy produced in Labrador.

As authorized by Québec Premier Daniel Johnson on October 6, 1966, Hydro-Québec put its trust in hydroelectric power: it agreed to purchase the energy produced at Churchill Falls to ensure that the full potential of this exceptional site would be developed.

Top of page1967

Founding of a world-class research institute

At the instigation of Lionel Boulet, Hydro-Québec decided to set up a world-class institute for research on electricity: the Institut de recherche en electricité du Québec (IREQ). Built at Varennes, where several 735-kV lines converge, IREQ initially consisted of about 60 general laboratories and one immense specialized laboratory, unique in the world, which was equipped to conduct experiments on high-voltage transmission and thereby provide the research to support Hydro-Québec’s high-voltage grid. IREQ opened its doors to university researchers and equipment manufacturers, who collaborated with Hydro-Québec engineers to develop the many complex components required by a 735-kV transmission system. Since IREQ was inaugurated in 1970, its researchers have continued to improve the performance of this technology, which even today—40 years down the road—still provides a level of efficiency that has never been equaled.

Slide show

The following slide show contains images from the year 1967

1968

Tracy, a legacy of Shawinigan Water and Power

Hydro-Québec went ahead with the commissioning of Tracy thermal generating station, which it had inherited when it took over Shawinigan Water and Power Company. In the early 1960s, when Jean Lesage’s government gave Hydro-Québec a mandate to develop all Québec rivers not already under concession to private developers, Shawinigan Water and Power had begun looking for other generating options that would allow it to continue expanding. It decided to build an oil-fired thermal plant at Tracy. A similar concern for diversification led it to acquire a substantial interest in Brinco, the private consortium in charge of developing Hamilton Falls (later renamed Churchill Falls), in Labrador.

Slide show

The following slide show contains images from the year 1968

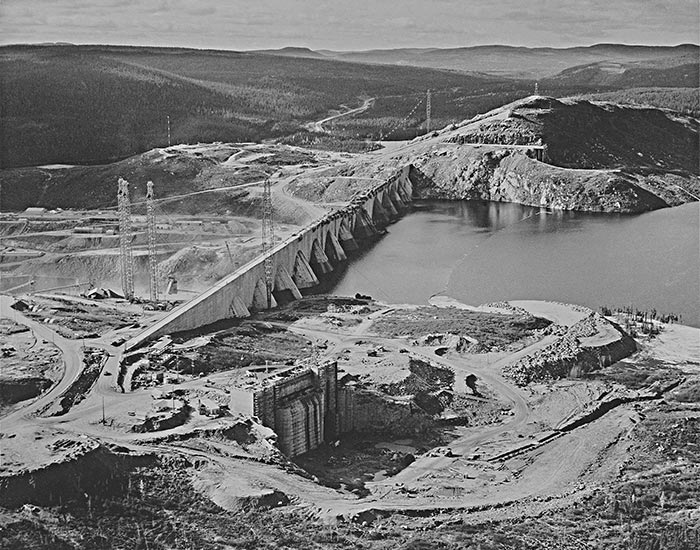

1971

At Baie James, the world’s largest hydroelectric complex

A work site of unimaginable proportions; a territory two-thirds the size of France, covering 350,000 km2; and the Grande Rivière, located 1,000 kilometres north of Montréal, surrounded by taiga and flowing over 800 kilometres from east to west. A logistical conundrum How to transport, within a reasonable time frame, all the machinery, materials and goods required to complete such a vast project? How to provide the workers with a minimum of comfort? The harsh climate had to be taken into account, as winters in the Baie-James region are long and cold. And the work site, because of its enormous size, posed all sorts of challenges: financing, concern for the environment, techniques for building in harsh surroundings, workers’ living conditions, and relations with Aboriginal people were among the issues that had to be addressed. Premier Robert Bourassa. launched "the project of the century" in April 1971.

"Project of the Century" – The La Grande Complex

The "project of the century", which took 25 years (1971-1996) to complete, had an eventful history in many respects.

-

Access to the work site

At first, a winter road and ice runways were used to bring in the materials required to start up the enormous work site. Later, a permanent road linking Baie-James to cities in southern Québec was built.

-

Management

Excluded at first from managing the project, Hydro-Québec had to insist on becoming the majority shareholder in Société d'énergie de la Baie James (SEBJ), a corporation created to oversee development of the Baie-James region's hydroelectric potential. SEBJ became a wholly owned subsidiary of Hydro-Québec in 1978. Since then, it has been in charge of managing major construction projects for Hydro-Québec, both within Québec and abroad.

-

The environnement

By virtue of its size, the project attracted the attention of ecologists here and all over the world. SEJB was careful to take environmental considerations into account, starting at the project planning stage. Later, mitigation measures of unprecedented scope were implemented to preserve the region's ecosystems. From an environmental standpoint, the thoroughness of the impact assessments conducted during construction made Baie-James one of the most closely studied regions on the face of the earth.

-

Relations with Aboriginal people

Only after long negotiations did the Cree and Inuit agree to the development of the rivers emptying into Baie James. They did so by signing the Baie James and Northern Québec Agreement until 1975.

-

Forced closures

Work had to be interrupted on three occasions: once because of a forest fire, once under court order, and once because of inter-union rivalry that degenerated into vandalism and resulted in partial destruction of the La Grande-2 work site, jeopardizing the project's target schedule.

-

Escalating costs

The galloping inflation of the 1970s and major changes in the technical configuration when the project was already under way made it necessary for SEBJ to revise project costs upward. This made financing on international markets more complex and resulted in larger electricity rate increases.

Despite the difficulties encountered along the way, Phase I of the La Grande complex was completed on time and within budget, adding four plants to Hydro-Québec's generating fleet: La Grande-2 (renamed Robert-Bourassa after the death of the former premier), La Grande-3 and La Grande-4. These three stations’ installed capacity (10,280 megawatts) is equal to the combined power of the Manic-Outardes complex and Churchill Falls.

Visit the Baie-James region and admire the power of the Grande Rivière. La Grande-1 generating station and the Robert-Bourassa development are open to the public.

Slide show

The following slide show contains images from the year 1971

1978

HQI, exporting unique expertise

For the first time in its 34 years of existence, the law that had created Hydro-Québec was amended. A board of directors replaced the former Québec Hydro-Electric Commission. The company was authorized to create a subsidiary, Hydro-Québec International (HQI), with a mandate to market the expertise of Hydro-Québec and its subsidiaries internationally and support efforts by Québec-based engineering firms to serve global markets, for the benefit of Québec society.

Mutual aid agreement between Québec and New York State

Hydro-Québec commissioned the first major 765-kV interconnection linking its power grid with the Power Authority of the State of New York (PASNY). Under a mutual aid agreement, the two parties agreed to support one another during peak demand periods, which they experience at different times of the year. Hydro-Québec could export substantial amounts of energy to New York State from June to October, while during the winter months, the American grid could send back all or part of the electricity it had received during the summer.

Top of page